Once upon a time, so we are told by the atomists of ancient Greece, triangular and star-shaped, round and sickle-moon atoms whirled about in outer space, with every atom finding its orbit in free fall and accidentally hooking up with others. Wild monsters with three trunks, free-floating uteruses and interlocked brain boxes flew through the emptiness of space, tangling into universes, blazing new suns and dying planets. Potential worlds, one after the other, kept taking shape until creation found rest of sorts and - as humankind hopes - a higher meaning.

The Greek atomists envisioned the works of writers being created in the same manner. According to Democritus, letters are atoms swirling about in chaos, where clouds of pure possibility converge into real works like Homer's Odyssey or Plato's Dialogues. Every book is the offspring of such chance encounters.

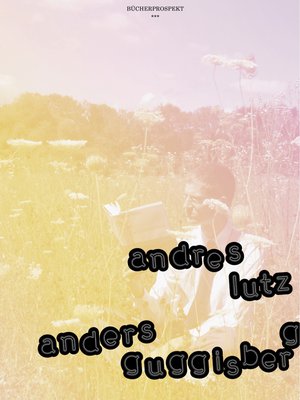

Hence, it is we, the readers, who invest this chance with meaning. First, we are struck by the title, the name of the author and possibly the publisher. That alone is enough to begin imagining a story, we can already smell the word worlds like sugar candy. It takes only a few pages for us to dream our way out of the book and back into our own minds. Into imaginary inner worlds, perhaps never even waking up until we find ourselves gazing at the imaginary Library of Lutz & Guggisberg: we hold their books in our hands, and, in doing so, we weigh the weight of our own imaginations.

Yes, the feel of their books is a delight, though we can only leaf through them in our own heads. They are unborn books, or, as the Talmud tells us, the child in the womb is a book that has neither been opened nor leafed through.

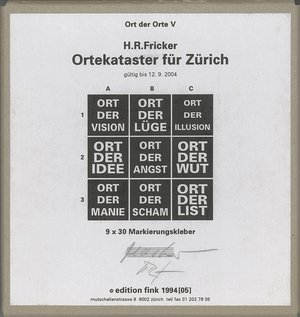

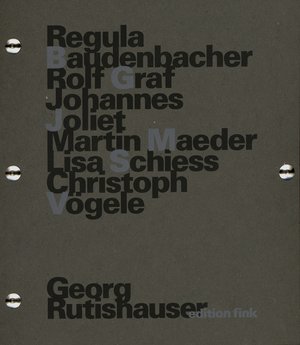

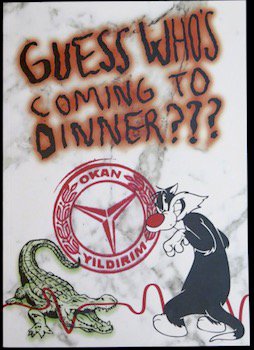

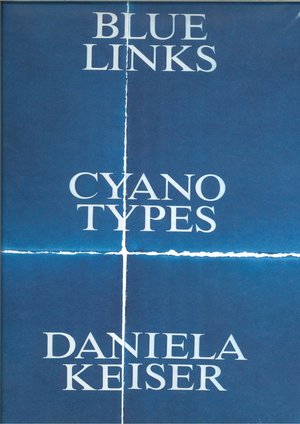

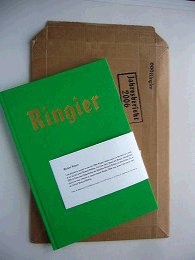

Lutz & Guggisberg have been working on their imaginary Library for years. In Exercises in Style, Raymond Queneau, the grand master of wordplay, wrote a dust jacket text for an unwritten book, another Lutz, graphic artist Hans Rudolf Lutz from Zürich, and Alex Sadkowsky once put together a catalogue of opening sentences and invented beginnings for novels. But now the jacket texts and sentenc-es have become objects, patiently sawed out of wood, beautifully printed and lined up on shelves.

The books of Lutz and Guggisberg pay homage to an almost extinct literary form: the so-called blurb. After lengthy detours, this curious literary species found its last refuge on the spine of books. Condemned to attract the attention of potential readers in large letters behind transparent plastic film, the blurb as a jacket text was reduced to monosyllables, "a masterpiece" or even, as the German doyen of literature Reich Ranicki once quipped, "a great masterpiece". But before sinking into the quicksand of idiocy, the blurb has spawned some notable purple prose. In the mid 18th century, a loose sheet of paper, a prospectus, was inserted in books, and in 19th-century France, the prière d'insérer acquired currency, a letter sent to editors-in-chief, asking them to publish the enclosed publicity text in their newspapers. Emile Zola once complained to Flaubert about the stupidity of one such text - albeit, without advising him that he himself had penned it. Flaubert kept meticulous watch on his blurbs. We imagine Bouvard and Pécuchet at the end of their turmoils, having dotted the garden of their estate with mighty watermelon heads, performed emergency operations on bloated calves and enlisted their educational methodology to raise two children and turn them into precocious criminals, we imagine them now proceeding to accumulate a kind of miscellany of the foolishness of their century by copying out bits and pieces from newspaper clippings and announcements - a scrap paper novel of surrealist proportions - before finally embarking on their ultimate hobby: inventing the spines of unwritten books. Lutz & Guggisberg may well be considered latter-day descendants of Bouvard and Pécuchet, perched behind their twin lectern in the kingdom of cross-eyed perception.

Look at them long enough and you will discover meaning in these rows of books, just as you might find meaning in the world. The name of an author makes an appearance elsewhere as a character in a novel, a blurb in one book refers to a word in the title of another. Yes, it is all here, the entire universe of chance and intent, gathered together in the free falling elementary particles of a new creation.

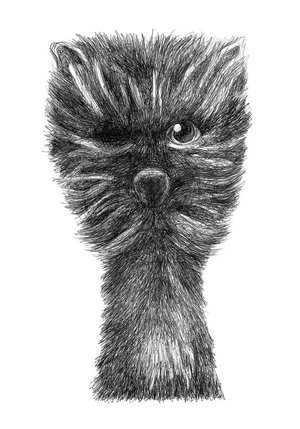

"Clinamen" is what the Greeks called the curve along which atoms fall. This clinamen, a curi-ous creature, makes an appearance in a novel by the French absinthe addict Alfred Jarry: it is a novel about a very special Doctor Faust, a Faust who does not make a pact with the devil, as Goethe has it, because the real world is not good enough for him, instead, he makes a pact with chance. And because the real world is not good enough for him, Jarry's Doctor Faustroll invents pataphysics. Pataphysics is the science of what cannot be known, it extends not only beyond physics but beyond metaphysics as well, or rather behind it: epi ta metaphysica. A "science of imaginary solutions", in which nonexistent solutions provide answers to nonexistent or at least unaskable questions. Pataphysicians learn to exercise their minds, ensuring that what occurs to them would never occur to anyone else. Except maybe to Andres Lutz and Anders Guggisberg. For ten years now, the two artists have been bombarding our senses with whey-like configurations, exploding display cases and trinkets from invented isles, about whose animal world we receive instruction from a kind of resurrected Hans A. Traber.

Dozens of tragedies by Sophocles have vanished, the second half of Gogol's Dead Souls went up in flames, and Nietzsche wrote Prefaces to Unwritten Works. Possibly these lost books or those that were never even written are the greatest masterpieces of all, as consummate as our fantasy in its deepest dreams. The body of a text rolls in endless rolls off the body of Doctor Faustroll: "Then the paper wallpaper came off Faustroll's corpse. Like a score, every art and every science was inscribed in the curves of the limbs, proclaiming their perfection all the way to infinity." One senses that infinity on getting lost in the imaginary Library of Lutz & Guggisberg. The Imaginary Library written by Stefan Zweifel (Translation by Catherine Schelbert)

Andres Lutz (1968) and Anders Guggisberg (1966) live and work in Zurich. The artist duo attracted international attention in solo exhibitions at Aargauer Kunsthaus in Aarau, at Museum Folkwang in Essen, at Centre Culturel Suisse in Paris, at Kunstverein Freiburg, at Villa Merkel in Esslingen, and at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham.