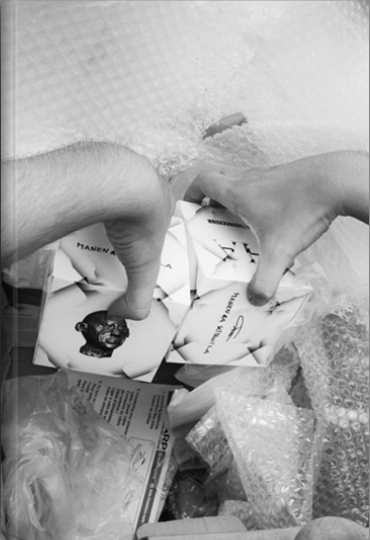

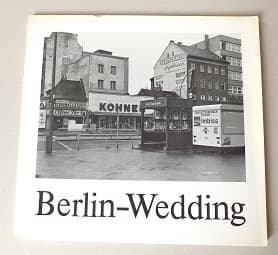

Having recently reviewed the contemporary street photography of Allen Wheatcroft, Body Language, and also having heard about the controversy surrounding the work of Butturini, I was certainly curious to take a closer look at this photobook as well. The book is marked “Edited by Martin Parr” on the cover, and he also wrote a page of introductory remarks for it, so I wanted to discover what this work was all about.

Gian Butturini was a graphic and interior designer from Italy who visited London for a trade show in 1969, and discovered photography at the same time (age 34). He was eager to capture the excitement of the times, and of course used the style of the period: black-and-white film photographs of people on the street, taken without their consent, as was customary and is still practiced by some today. In that same year the book resulting from his project was self-published in Italy in an edition of only 1000 copies. After Butturini’s death, Martin Parr discovered this work as part of his research on photographic projects involving London, and was instrumental in having this facsimile edition, a reprint of the original, published in 2017.

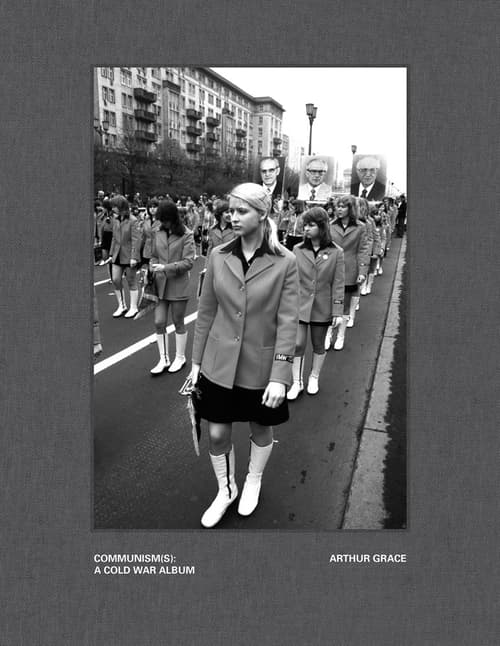

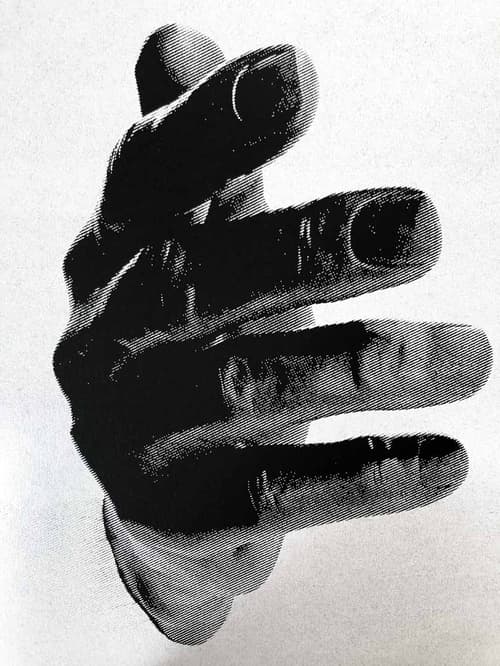

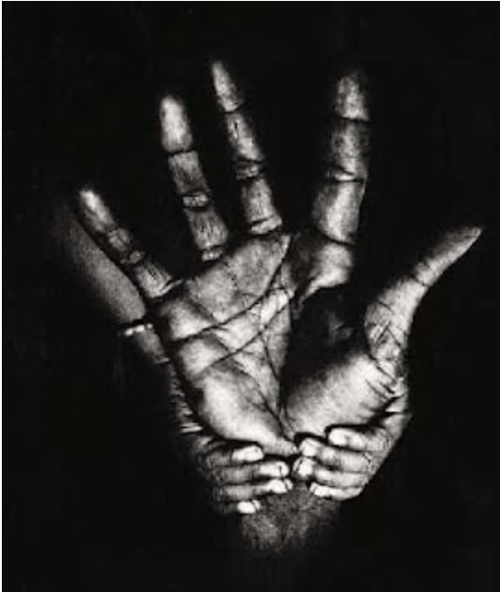

Butturini’s style of street photography and this photobook are representative of an older, in-your-face presentation of social and political elements, using a form of presentation that is heavily influenced by graphic design. In the preface Parr states that “Butturini wanted to make a politically charged book … The startling thing about the London book is the strong grainy quality of the images woven through with the graphics of the same period … he combined all kinds of tricks to build his narrative, from graphics, torn paper, drawings and small blow-ups of details of his images.”

This kind of street photography reminds us of some of the images of Garry Winogrand, or Moriyama, or Bruce Gilden’s in-your-face method of depicting the street. Indeed, we see all kinds of people from different ethnic and socioeconomic groups, and the overall effect strikes us as rather dreary from our present perspective. This was the time of the Vietnam War, and protesters were active in London as well. We see all kinds of political persuasions represented.

The graininess, partly caused by extreme enlargements, makes some of the figures very indistinct, and, combined with unflattering lighting, erases distinctions, so that we are at times unable to see what skin color a person has. That’s certainly a welcome side benefit. The concentration on the less fortunate that are contrasted with the well-to-do may be an oversimplification that has been somewhat overcome in contemporary street photography.

And as far as unfortunate or insensitive juxtapositions are concerned: How dated is it, for example, to call a grown woman a “girl” or to juxtapose a gawking guy with a picture of two women? For a spirited discussion of the black lady selling tickets in a glass cage on a double page with a caged gorilla in the zoo, both depicted as victims of their circumstances, I refer you to Douglas Stockdale’s Singular Images, as discussed here. I think it is a mistake to cut out part of history, including the history of photography, just because we see things more comprehensively in our time. Clichés and prejudices as depicted can be a great basis for discussing what was wrong then and needs to be improved even in our time. When such products as this book are withdrawn from the market, we are removing valuable opportunities to have a rigorous examination of where we as a people have been and where we need to go from here.