It all began in Salins, where humans exploited salt water from natural sources as early as the Middle Ages. The brine was heated and salt obtained after evaporation, requiring vast quantities of wood as fuel.

In the middle of the 18th century, demand for salt increased due to demographic growth (new requirements for cured meats, cheese-making, certain craft activities such as tanneries, etc.), not forgetting the commitments made by the kingdom of France to supply the neighbouring Swiss cantons with salt. The kingdom was also interested in increasing salt production because it brought in tax revenues thanks to the salt tax, known as the Gabelle tax. All of these elements contributed to the creation and the construction of a new saltworks, in an ideal location close to Salins and large reserves of wood. A large flat area was chosen between the villages of Arc and Senans, around 20 kilometres from Salins and next to the immense Chaux forest.

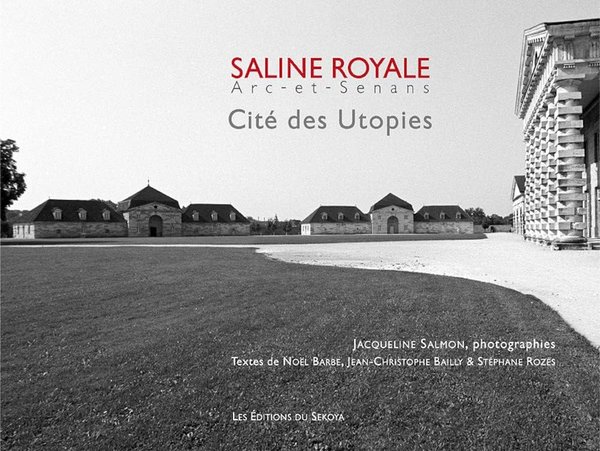

Here, between 1775 and 1779, the 11 buildings of a “Saline royale” were built, treating the salt water transported from Salins through a double pipe (called “brine pipeline”), which originally consisted of hollowed-out spruce trunks stacked inside each other (replaced soon after with iron piping), buried one metre underground.

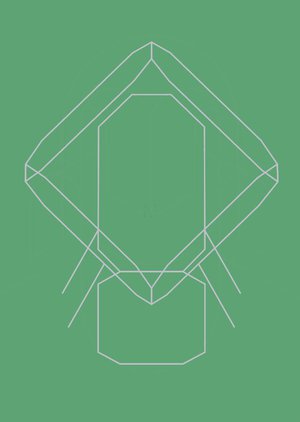

The decision was made under the reign of Louis XV and the design of the new Saline royal was commissioned to Claude Nicolas Ledoux, an architect close to the royal court and undoubtedly one of the most prolific of the late 18th century. After his first project was rejected by Louis XV, Claude Nicolas Ledoux proposed a collection of buildings arranged in a perfect semi-circle, with the East-West diameter formed of salt production buildings, the director’s house and the Clerks and Gabelle lodges.

Strongly inspired by the philosophers of the Enlightenment, the architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux defended the idea that architecture was a source of transformation for society. His ideal city project, of which the Royal Saltworks was one of the essential components, reflects his ambitions.

The new factory was created as a real production unit incorporating two large buildings (known as the “Pan houses”) where the brine was evaporated, one building for the blacksmiths to work (the Farrier), and another dedicated to making barrels (the Cooperage). Additionally there was an entry and control building (the Guards), residential buildings (the Berniers) and two lodges for administration (the Clerks) and tax (the Gabelle). The site, in the shape of a perfect semi-circle, is dominated by the tall columns and the pediment of the “Director’s House”, flanked at the back of a small, harmonious building constituting the stables of this same house.

As splendid as the architecture of the site was, economic success was unfortunately not forthcoming and the originally-planned production of 60,000 quintals of salt was never reached, even in the 19th century when construction of the railway made it possible to supply the Saline Royale with coal (and no longer wood) to heat the brine. Technical improvements, developments to the exploitation method and changes in ownership linked to political developments in France did not bring about the expected profitability. In 1895, the “Compagnie des Salines de l’Est” decided to stop production of this “evaporated” salt which, additionally, due to leaks in the brine pipeline, had made the well water of Arc-et-Senans brackish.

In December 1982, the Saline royale of Arc-et-Senans became a UNESCO World Heritage site, making it the 12th site in France and the 150th site worldwide to be listed.