Publisher Note

The sound of each individual’s voice is thought to be entirely unique. Like a fingerprint, its composition is distinct, nuanced, and one-of-a-kind. While all this is true, it’s a concept that has been challenged in recent times by the refinement of AI-powered systems which are able to emulate voices to a tee. And not only voices, for that matter, but whole styles and aesthetics: an AI-generated facsimile of Drake and The Weeknd’s voices titled “Heart on My Sleeve” made the rounds this year and was even submitted for Grammy consideration. It’s a legitimate song, and a proposal that does not only keep legal departments busy, but also allows for myriad reflections on originality and, bluntly, the future of music. But as the future of music is a broad and daunting topic to speculate on, we want to hone in on what’s been prefaced above: issue #28 of zweikommasieben centers the voice as means of expression, and wants to expand on what is meant by that: it’s not only what is heard, but also why a voice is used and by whom. This latest edition considers what it means to voice, and its physical, societal and political dimensions.

Truthfully, voices as a topic might be even more daunting to tackle. Its political implications are manifold and have to be considered in seriousness. Voice can’t be separated from reflections on the ingrained power of attitudes, beliefs, and norms that dominate. Exhibit A for these complex entanglements is a conversation Dounia Biedermann had with South Korean artist bela. The musician explains how they use all kinds of different voices other than their recognizable speaking voice to articulate and access deeply felt emotions towards their home country and identity. “Whispering, growling, screeching, and inhaling” help them in disrupting cultural boundaries of power that historically constrain and silence marginalized identities. With this approach, bela finds an ally in Krista Papista: in conversation with Jazmina Figueroa she informs that her latest album was an explicit tribute to the lives of victims of femicide in Cyprus, and the marginalized voices that are not heard within the Cypriot national ideology. By subverting traditional music genres and poetics, both Krista Papista and bela push forward the need to queer history and to reveal longstanding, harmful, national myths.

In a queer history, we are no longer pointed towards dominant and singular voices, but instead expand to a context that is polyvocal—a term we encounter in artist Claudia Pagès’ contribution to this issue: through the tools of light, drums, and text, a different temporality and reading of history is proposed. Tuning out of the prevailing source of authoritarian speech, and tuning in to the voices of many, also leads us to consider the articulation of the collective. In his interview with Helena Julian, artist Tianzhuo Chen points to the shared voice of humankind as a whole, and its yearning for a state of flow and togetherness.

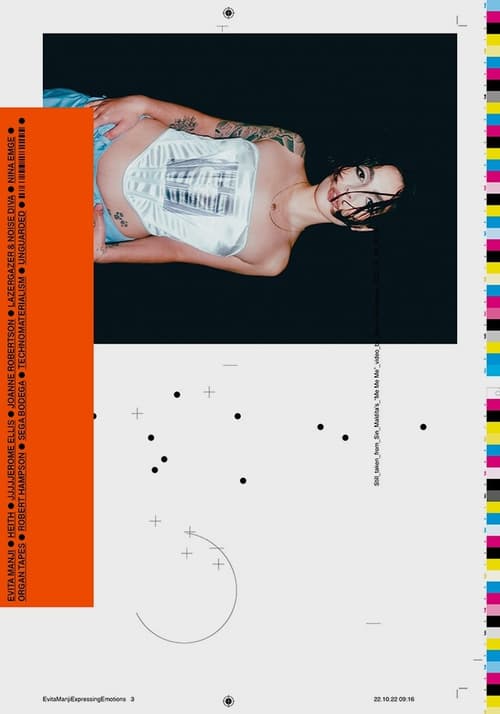

For the latest iteration of the visual column “Formations”, Imane Djamil provides a portfolio of photographs taken in the Moroccan seaside town Tarfaya. In the series, we are confronted with the boundaries that can be imposed on one’s legitimacy to express. We witness glimpses of everyday life, in close proximity to the severely precarious migratory sea passage towards Europe. Hearing the voice of the local community, we equally become aware of whose voice is missing.

Naturally, the voice is also an instrument that is shaped by its limitations. Although, still today, it seems to have preeminence above all other forms of human expression. The full width of the use of voice and sounds produced by individuals is further explored in an essay by Dagmar Bosma. The artist and writer muses on the act and appearances of different forms of stimming, which is a verb that originates from the neurodivergent community. Bosma highlights the sonic dimension of stimming with its vocalizations and repetitions of sounds and rhythms, as a way to equally express and soothe.

A recurring interest of zweikommasieben is, to speak with Claudia Pagès, to be polyvocal. Previous issues tried to achieve this by highlighting all the different people involved in bringing a magazine to life (in issue #22) or allowing authors, translators, photographers, and designers to make additional editorial notes (in issue #23). This time around, the graphic designers Kaj Lehmann and Raphael Schoen are using typographic matter to create a similar effect: different cuts of the same font (which was designed by Lehmann and previously used in issue #17) are applied to choral effect.

One could argue that for a voice to exist, it needs to be heard. In this 28th edition, we wish to offer exactly that. In the next pages, you will perceive a multitude of voices—from roars to whispers—, sometimes out of tune or out of time, with the intention to be recognised by those who dare to listen.

zweikommasieben Magazin #28

| Publisher | |

|---|---|

| Release Date | December 2023 |

| Series | zweikommasieben, #28 |

| Work | |

|---|---|

| Subform | Music Magazine |

| Topics | Experimental Music, Music, Pop Music, Voices |

featured in

Hold The Sound